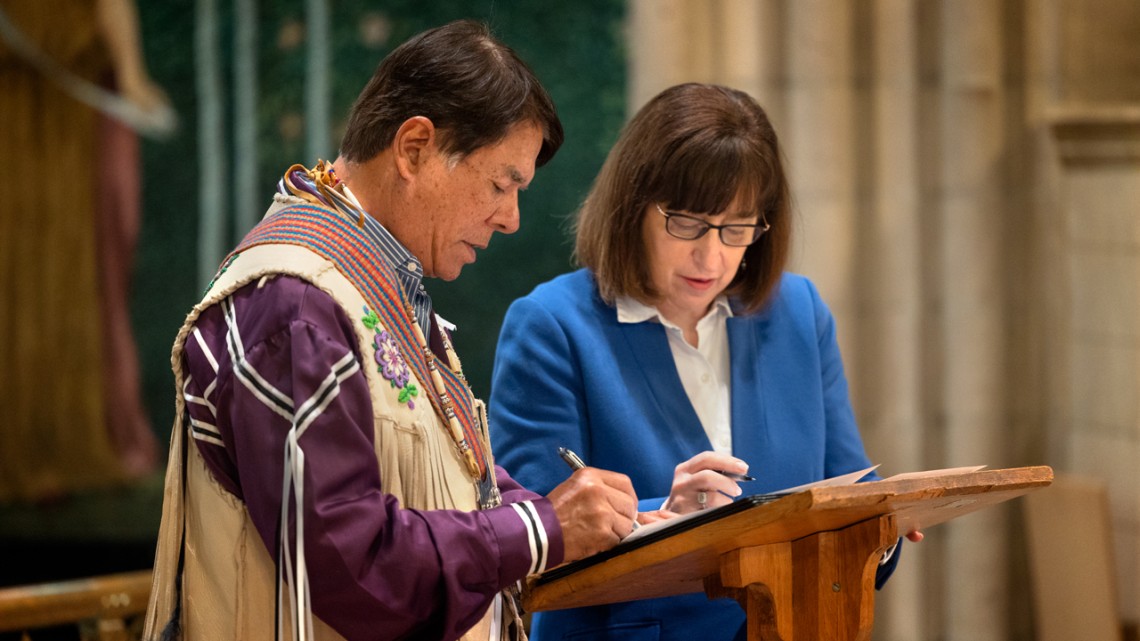

Photo by Jason Koski/Cornell University

Ray Halbritter, left, representing the Oneida Indian Nation, and President Martha E. Pollack, sign documents that repatriate ancestral remains from the university to the Oneida Indian Nation.

Cornell repatriates ancestral remains to Oneida Indian Nation

With apologies for causing harm and in an effort to right the wrongs of the past, Cornell returned ancestral remains and possessions that had been kept in a university archive for six decades to the Oneida Indian Nation on Feb. 21 at a small campus ceremony.

The remains were unearthed in 1964 as property owners dug a ditch for a new water line on their farm near Windsor, New York. Law enforcement authorities brought the remains to a Cornell anthropology professor, who carried out forensic identification for age and sex. The remains were then stored in a campus archive until after the professor’s death – only to be rediscovered by younger colleagues during an archival inventory.

“Today we’re marking an event that is both long overdue and never should have become necessary,” said President Martha E. Pollack, speaking at the Sage Chapel ceremony, where faculty, students, staff and Oneida Indian Nation guests gathered. “We’re returning ancestral remains and possessions that we now recognize never should have been taken; never should have come to Cornell; and never should have been kept here.

“We are here to try – as far as we are able – to right those wrongs,” Pollack said. “In doing so, we take responsibility for them and we grieve the harm they have caused.”

Ray Halbritter, Oneida Indian Nation representative, said that the individuals will be laid to rest in the tradition of their people. “We are finally able to speak to them in Onyota’a:ká:, the Oneida language – the language they would have spoken during their lifetimes,” he said.

“The return of our ancestors to our sacred homelands is a basic human right,” Halbritter said. “We commend Cornell University for working with the Oneida Indian Nation to right this wrong. The repatriation of our ancestors’ remains enables us to honor their lives and honor the ways that our people have lived by since time immemorial.

“Each time the remains of our ancestors and our cultural artifacts are returned to us in this way, we take another step forward in a long journey toward recognition of our sovereignty as a nation and our dignity as people,” he said.

At the ceremony’s end, Pollack and Halbritter each signed transfer documents.

Funerary objects that were interred with the ancestors will be restored to the Oneida people as well.

The event included traditional Oneida ceremonial words delivered by Dean Lyons, an Oneida Nation Turtle Clan member. Lyons was introduced by Joel M. Malina, vice president for university relations, who opened the ceremony with the acknowledgement that Cornell is located on the traditional lands of the Gayogo̱hó:nǫɁ people.

“Nearly sixty years ago, these ancestors were taken from the place their families chose for them,” Pollack said. “Without regard for the wishes of their descendants, they were taken to Cornell and remained here for decades – unidentified, alone and far from the places and people among whom they belonged.

“Today, I want to apologize, on behalf of the university and all who were involved in these wrongs, for the disrespect shown to these ancestors,” she said, “and for the hurt that has added more pain to the tragedy of Indigenous dispossession.”

The ancestral remains came into the possession of the late anthropology professor Kenneth A.R. Kennedy in 1964 – a quarter of a century before the passage of the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990. This law provides a formal process for institutions to repatriate cultural items or ancestral remains to either lineal descendants or tribes.

“To say that Professor Kennedy’s actions were utterly commonplace among his contemporaries is not to excuse them,” said Matthew Velasco, assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, in the College of Arts and Sciences, speaking at the ceremony. “On the contrary, they reveal the mundanity and pervasiveness of Indigenous dispossession.”

Velasco, as an educator and researcher, explained that he is an inheritor of this legacy: “Our efforts to help bring the ancestors home cannot erase the harm done,” he said. “But I hope this serves as a sign of our remorse, our respect for the Oneida Indian Nation and our resolve to do better.”